The Scholia in Apocalypsin

The Scholia in Apocalypsin

Cassian the Sabaite was not the Scythian of Marseilles. It was another Cassian, more than a hundred years later than that ‘Scythian’ figment. This was a monk of the Laura of Sabas in Palestine, coming from Scythopolis, a town of Koile Syria closely affiliated with Antioch, a student of the sixth-century ‘Origenism’ (of which Origen was all but the father), certainly of Didymus, and most certainly of Evagrius. He was a spiritual son of St. Sabas, the famous founder of the Great Laura. Cassian was the founder of the Zouga monastery in his native Scythopolis in Palestine, and the abbot of another one in 540-547 (the Souka monastery, or the covenant of Chariton, on which light was cast by recent archaeological excavations during the 1990s). Finally, he became the abbot of the Great Laura of Sabas in 548, only to remain in the post for ten months until his death on the 20th July, in 548 AD.

Cassian was a close friend of Leontius of Byzantium, a sixth-century ‘Origenist’ and protagonist in the so-called ‘Origenistic-controversy’ of the period in Palestine, who took part in the local synod of 546 in Constantinople, where Cassian was present, too. They both signed the synodical acts. To this Leontius Cassian’s works are addressed. These works are now being published in a Greek edition, along with an English translation. The results, comparing terms and expressions from all Greek literature, both pagan and Christian, are stunning. The Greek text is not, and cannot be, a Greek translation from the Latin. This is a Greek original, full of technical terminology, both Classical Greek and Patristic literature. This is another Cassian, unknown and nonexistent to scholarship thus far.

Further investigation showed that no Greek author (from the sixth to fourteenth century) knows of any ‘John Cassian’, the alleged fourth-fifth century deacon of John Chrysostom. They all know of Cassian and mention him in admiration as the ‘great Cassian’. However, he has been eclipsed by the Scythian John Cassian of Marseilles, by means of tampering with manuscripts (indeed extinguishing ancient Greek ones) and heavily interpolating the works ascribed to him in the Patrologia Latina, and in the Vieanna corpus of the Latin authors. He has been advertised as the father of the Benedictine monastic order and as ‘the sole Latin Father included in the Philocalia’, that is, the anthology complied by Nicodemus of Athos. All these are simply a myth conspiring to establish the presence of a figment called ‘John Cassian’ instead of the real one. namely, Cassian the Sabaite.

The comparative study of Cassian’s Greek works in Codex 573 and the Scholia (that is, a comparison of Codex, pp. 1-120 and 245-90) provided me with the final conclusion. Monk Cassian the Sabaite is the compiler of the Scholia in Apocalypsin.

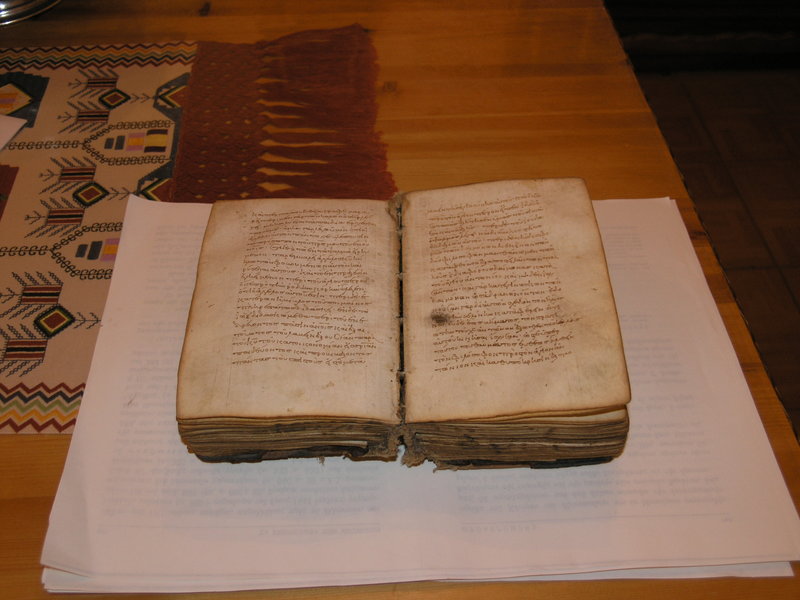

The text of the Revelation and the Scholia are part of a cursive manuscript included in Codex 573, conserved in the monastery of Metamorphosis, in Meteora, Thessaly. This Codex is an exquisite piece of art: the ‘Book of Cassian’ is made of fine leafs of parchment; the binding is wood-plates covered with leather, whereas the clip keeping the book closed is also a fine bronze buckle. There are 290 folios (dimensions: 0,12 x 0,185), which also contain other noteworthy material, such as Hippolytus’ On the Blessings of Jacob (ascribed to Irenaeus in the title of this MS). The text of Revelation occupies folios 210r to 245r. The Codex is considered to be a tenth-century manuscript, yet my own assessment is that this is an early ninth-century one.

Codex 573 is a product of the milieu of the Monastery of Saint Sabas near Jerusalem. An investigation in the Patriarchal Library in Jerusalem (where the Sabaite manuscripts were transferred a hundred years ago) shows that no scribe named Theodosius appears. This name appears in the Meteora-Codex 573 only. However, it turns out that the same hand wrote at least two more Sabaite Codices (St. Sabas 76 & 8). Which makes the scribe of the Jerusalem codices identifiable: he was monk Theodosius. Nevertheless, philological exploration shows that the content of this ‘Book of Cassian’ was definitely known to the monastery of Studios and Theodore Studites himself. For it turns out that exquisite parallels to Cassian’s text transpire frequently in the work of Theodore Studites. Theodore is the man who had built the most renowned scriptorium of his times in the monastery of Studios. This institution was in many respects the heir of the Akoimetoi, certainly the heir to their vast library, which was affluently reproduced therein. Cassian was one of the Akoimetoi and, given the close contact between them and Palestine, his book should have been made available to them and reproduced in their library.

The Scholia are in fact notes and remarks by Cassian, who did not seek to offer any comprehensive commentary on the Apocalypse. His only aim was to establish the authority of the Book of Revelation as canonical. Those notes are personal reflections on how the exposition on the Book of Revelation neatly fits into the entire truth and continuity of both Testaments. Nevertheless, although only notes, they are written as a continuous text. Cassian resolved that the Revelation is a divinely inspired book and this attitude permeates the text from start to finish. It seems that the original was not written in the form of the apocalyptic text accompanied by remarks written in the margin; for some Scholia are too extensive for them possibly to have been written in margins. The author quotes passage after passage and comments on each in turn, in a text so continuous that there is no change of paragraph when he moves from the conclusion of one Scholion to the quotation of the ensuing passage of Revelation. This set of comments seems to have been intended for personal use. Cassian probably composed this also as part of his pastoral care as an abbot, in order to provide his monks with arguments buttressing up the canonicity of Revelation.

Although the exposition is not desultory, the aim of the author is not to offer a comprehensive account of any aspect of the doctrine. Rather, the reader (or, the audience) is given to understand how the truth of the entire Holy Writ is instantiated in the narrative of John. There is scant regard paid to the theological debate of his day. On the whole, the text is a double accolade for both the Revelation itself and Didymus, who had cast light on the apocalyptic narration, which otherwise could have appeared as either arcane or exotic. Since differences in style between different scriptural books is already there, the idiosyncratic character of this revelation appears to be contrapuntal rather than contradictory in respect of the rest of Bible. In this holy polyphony, John’s text is the peroration of a speech that commenced ‘In the beginning’ of Genesis and was somehow reiterated ‘In the beginning’ of John’s gospel. Considering the eschatological vision, the Pantocrator who is enthroned on high is the same one as the Resurrected One, who was restored to his glory after having been made ‘a little lower than the angels’, he is indeed the selfsame person of the Trinity who jointly uttered the demiurgic fiat. Furthermore, the honorific designation Pantocrator is one that safeguards one more point of unity between the two Testaments, since this Septuagintal epithet hardly ever appears in the New Testament, and 2 Cor. 6:18 is only an Old Testament-quotation. This pregnant appellation is one of the points of this Revelation contributing to the New Testament, as Didymus had pointed out.

In Didymus Cassian found a reliable preceptor on the book of Revelation, who also happened to be an Aristotelian scholar. Hence, in the hands of Cassian, Didymus’ commentary added a cluster of further arguments that conspired to establish the book as an inalienable part of the Holy Writ. It has to be said, though, that Cassian did not rest content with the commentary of Didymus only. He availed himself off all his personal erudition and knowledge of the previous Patristic period. Canvassing the language of the Scholia reveals debts to certain Christian theologians, from whom he picked up passages suiting his own purpose. These passages were culled from various works: in the first place, each of their authors had not penned them as comments on Revelation, but on different points or books of scripture. As a matter of fact, no catena on Revelation has ever been composed, which is indicative of the prolonged ambivalence vis-à-vis this book.

The vatic manner in which the text is enjoined is coupled with its apposition to analogous scriptural passages showing that there is an indefeasible message to be conveyed. Cassian in effect tells us that no forfeiture of either reason, or ‘the mind of Christ’, is entailed once we acquiesce in this specific revelation. The message of the Scholia is then that they are not any sort of oracle: we read an intellectual who arrives at his exegeses by rational processes; he is not an hierophant who delivers obscure oracles amidst Delphic smoke. Even if the asseverations of the book were taken as an omen, this is only the premise in an argument, or epilogue to a conclusion, that can at the same time be reached by exegesis or indeed by ratiocination. No matter what the pictures the author borrows to portray his message, all the aspects of it sit cheek by jowl with elements of the two Testaments and of Patristic lore.

Opting for allegorical rather than typological exegesis suggests that the author explores the theological rather than historical message of the text. Cassian did not concern himself with any veridical resemblance of the narration in Revelation with the historical reality surrounding either him or that of his ancestors. Had he attempted to produce substitutes for the literal meaning, he would have fallen short of symbols prefiguring the world of the near or distant future, which has been the craving of many people approaching the apocalyptic text during the last two thousand years. In contrast, all we actually have is the homology of the one and same Christian love. Cassian points out the sameness, not the otherness, of this message in the apocalyptic text. There is nothing startlingly new in this text –which is what vouchsafes its authority. Consequently, no need for furnishing hermeneutic rainbows is felt by the author. True, no scriptural text is couched in such awe-inspiring pictures. However, were the veil concealing this text torn away, and the text become diaphanous, the messages that would emerge are already present in the New Testament. This is the quintessential consistency of the text.

The main concern is about the eternal prototype ‘sitting on the throne’ and the voice adumbrating the eschatological reality, not about speculative numerology on the ‘name’ of the beast. The writer of the Scholia addresses himself to the real question, which is this: is the spirit of the Scholia the same as that which permeates the Old Testament, where the occluded mystery of salvation was tacitly but ubiquitously prefigured, somehow present and still awaiting the Incarnation in order for this old text to be illuminated? Is the obscurity in the apocalyptic text of the same nature and, in its turn, is this text pregnant with eschatological anticipation?

Cassian does nothing more, yet nothing less, than show that the Holy Spirit is present throughout. For all his immense knowledgeability, his approach is an all but pedantic one: he searches for the truth that shapes the words, not the verbal canopy making up the text. The comments are designed so as to leave the reader with the afterglow of the apocalyptic epiphany, and with the anticipated universal sharing of this reality, not with barren concern about beasts, dragons, and arithmetised names. Granted, the text is enigmatic, it is cryptic, its message is cloaked in riddles. But this only serves as to stir the mind to reflection. This is how not only John, but also Jesus, couched much of his teaching. If we are to do away with the arid literal form of the text, we must embark on a specific kind of reading, for which the precedent of the great Alexandrians is the prototype and catalyst.

This prototype Cassian followed skilfully, yet sensibly. For all his learning and scholarship (and probably because of them), he adduces no extraneous wisdom: he only elicits what the Logos has already made incarnate in the text of scripture. This is the epitome of the exegetical method and the hermeneutic key to unlocking Revelation’s latent truth. No fanciful substitution of the elements of the vision by modern or ancient historical realities is furnished at all. Through such imagery, which for two thousand years has been styled ‘apocalyptic’, we descry another world.

The Scholia evince that Cassian found Revelation consonant with the entire theology of scripture and sought to authorize each passage by quoting invariably from both Testaments. He did not set out to disclose the apocalyptic content of the scriptural text in its own right. Neither did he see this as cryptic imagery which needed to be deciphered, which is a sport favoured by modern readers of Revelation. Cassian did not make it an ad hoc task to see the eschatological, or indeed the historical, connotations of the text itself. All he did was to find out and establish how this text is (in both essence and function) related to the rest of scripture, and to expound considerations which prove it concordant with this corpus. If particular passages of the text express in essence what other writers of the Bible do in their own manner, vocabulary, or imagery, this should be a sound reason for establishing the last book of the New Testament as a canonical one.

Although the Scholia could eventually crystallize into a commentary, this was not actually necessary. One does not need to deduce an entire philosophy of history, or an entire eschatology, out of this text, just as that one would not require this from a single catholic epistle. This is why extracts are culled in order to show that the passages are in tune with canonical scripture.

The Scholia derive their merit, both severally and collectively, from the scripture. Far from being the whim of an angry, or hopeful, or hallucinated, member of the church of Ephesus, the Book is shown through careful reasoning to partake of the same wisdom as any other book in the corpus and is thus as susceptible of theological gloss.

Cassian is here a monk, a scholar and a theologian, as he is in the rest of his writings included in the Codex. The lesson he teaches is that the Canon should be built following reasonable reflection, and that there is ample room to do so. To reject the Revelation out of hand on the grounds of philology (as Dionysius of Alexandria did) might be ill considered; to accept it unthoughtfully would be temerity. Nevertheless, being an abbot, he was an officer assigned with the duty to shepherd the transmission of the original deposit. Therefore, he also said things concerning doctrinal aberration, which he felt a Christian theologian must gainsay.

It cannot be denied that the Scholia radiate the aura of Origen, but in almost all instances his commanding influence is filtered through later enthusiasts, such as Eusebius, Gregory of Nyssa, or Didymus. The exposition is authoritative since it unfailingly yields testimony to Christ. The Scholia give off the ubiquitous aroma of the scriptures showing the text of John to be in harmony with them all. The message imparted is the same as any commentary which does not do away with the kerygma, but draws on the same reservoir of faith. Therefore, the Scholia effect a spiritual pendant, a diadem, attached to the Revelation and ushering it into canonicity. They are not heterogeneous with respect to the rest of scripture, which vouches for its divine inspiration and therefore canonicity.

It is reasonable for Cassian to pay his dues to the Evangelist. The Apocalypse is not scriptural because John the Theologos wrote it. But since it is shown to be a scriptural book, and given its date, John the Theologos is the author. It is the Spirit and his message that allows the author of the Apocalypse to be recognized; it is not the author who will grant authority to the book.

The rationale for Cassian’s aim to establish the authority of Revolution should not elude us. Even if the style of the book were like that of the gospel of John (which it is not), this would not suffice to make it canonical on that account alone. It is divinely inspired because its content (rather than its signature) makes it an integral part of the scripture. Being a good student of Origen, Cassian knew the lesson which the Alexandrian had taught: Scripture is held to be divinely inspired, but it is not itself deified. It is not the case of the Biblical corpus being made an idol. What has to be comprehended therein in the first place is life, as an uninterrupted consequence of historical events, through which God speaks to men. What is assumed to be ‘hidden’ in scripture is ‘the mind of Christ’ which cast light upon the meaning of History, the significance of particular events that took place during the peripeteiae of the ‘people of God’. No part of creation (including the sriptural writings themselves) is elevated to the point of being regarded as something unconditional, unqualified, unrestricted, indeed as something absolute, in the sense of a self-contained idol, a golden calf, as it were. On the contrary, everything is placed and understood within the context of the metamorphotic course withing the Church. This is the locus where the Uncreated and the Created reality encounter each other; it is there that the ‘mystery of the Church’ takes place as a reality which is both historical and eschatological; it is there that everyone can participate in this encounter through the action of sacraments. Thus the Scripture, is indeed an object of reverence, not because it is considered to be in itself a kind of idol, but because ‘the holy letters’ is the point of departure for us to become able to ‘construct’ the recorded events ‘out of them’: which means to reconstruct the events through which God manifested himself and intervened in History, and the faithful experience the significance of such events within the Church. In short, Scripture is highly valued, because through this we can reconstruct and understand God’s action. Through Scripturen ‘the doctrine is standing as the doctrine of God, and Jesus is proven to be Son of God both before he was incarnated and after he was incarnated’, but this is so only because divine action is comprehended in all of its cosmic implications, not because an insightful intellectual deciphered the ‘meaning of the letter’ as if it were a cryptic ambiguous oracle. On that account, the reader of the Scholia must pay particular attention to the fact that Cassian stives to establish the divine character of the Revelation by appealing to events rather than concepts of the scripture, normally citing instances from both Testaments for each Scholion.

The passages of Revelation corresponding to the specific Scholia are not of equal length. By the end of the notes, we come upon extensive passages of Revelation with relatively short comments. This may in fact not be the result of a rational decision. As the author progresses in establishing the canonical accord of the Book with the rest of scripture, he feels he needs less and less to make detailed comments on short passages of the Revelation. The book is no longer scrutinised phrase by phrase, or in small passages, as it is in the beginning. As he goes on, Cassian feels he has supplied sufficient argument. Happy as he is about this, he skips large passages of the Book or makes short comments on them. His task had been fulfilled. The Book had already been shown to be nothing less than a full exposition of Christian Truth as found in the rest of scripture. The scholia are not actually unfinished.

So, what we have is not a commentary, but Scholia, or notes, on the sacred text read by Cassian. In fact they are adnotationes in Apocalypsin. They are personal notes of an erudite scholar, which, however, are not meant for personal use only. They were probably intended for circulation among the monks of his coenobium, as well as the rest of his brethren, both locally and in Constantinople. This is why this text is found in a Codex that aims to fulfill personal spiritual needs of monks in the region of Palestine, that is, in the region where the authority of Revelation had been strongly resisted for a long time.

Cassian did not finish, and did not need to finish, his notes on John’s text. Given his aims, he did not need or intend to write a commentary on the entire Book of Revelation. The commentary was already there, written by Didymus. Cassian more or less quoted from this lost Commentary on the Apocalypse of John. One Scholion (the fifth one) is a verbatim quotation from a text by Clement of Alexandria. Some Scholia are mainly annotations of his own, which draw on his personal readings of writers such as Origen, Eusebius, and Gregory of Nyssa (probably his reported, and now lost, orations on the Apocalypse), as well as Aristotle, Alexander of Aphrodisias, Plutarch, Galen, and others. In Scholion XXX, Theodoret’s personal seal for posterity to detect him is quoted: ‘as indeed we have taught in our exegeses of 1 Paralipomenon’.

The philological analysis of the Scholia brings to the fore the influence of Diodore of Tarsus, Theodore of Mopsuestia and Severianus of Gabala, in short, what has been known as the Antiochene School. Moreover, there is the commanding presence of Didymus (whose commentary is heavily quoted), whereas echoes of Eusebius and Gregory of Nyssa are clearly noticeable. On the whole, the Scholia make clear how obsolete the distinction between the Alexandrian and Antiochene schools was in the middle of the sixth century. Clearly the Antiochenes always revered the legacy of the eminent Alexandrians. This holds particularly true for Theodoret and Cassian, who appear to be genuine heirs to Origen’s textual explorations. In any event (and beyond this or that quotation from either Didymus or Clement, or of remarks of his own evincing his philosophical, and theological depts to specific figures, such as Eusebius, Gregory of Nyssa, or Theodore of Mopsuestia), Cassian allows his spiritual ancestor Theodoret to speak for himself and put his personal signature upon those Scholia. This is the revealing remark he makes in Scholion XXX: “as we have taught in [our exegesis] from the First [book] of the Paralipomenon”. No theologian other than Theodoret ever produced a commentary on this scriptural book. In addition, the exegesis he produced on the difficult similarity between 2 Kings, 24, 1 and 1 Paralipomenon 21, 1 stands out in Christian exegesis and was praised by Photius.

The initial edition

The Scholia, in the form edited and published by A. Harnack and C. Diobouniotis in 1911, have never been unanimously accepted as a work of Origen’s. Nevertheless, too much has been made of Origen’s mention of a commentary on the Revelation he purpoterdly wrote. No allowance has been made for the possibility that Origen eventually may have been unable or unwilling to go ahead with this project, or to satisfy himself with the fact that (virtually) the entire commentary on Revelation ipso facto was included in his commentary on the gospel of John. It seems, however, that this statement was fatal to the position of Harnack, who resolved to ascribe the Scholia to Origen. Some scholars (inevitably taking into account the prestige of this busy authority) employed Harnack’s attribution to Origen; others appeared hesitant and only a few were dismissive. This set of Scholia then lay fallow, and the text itself is, to date, of no avail to scholarship. Harnack was in fact all too quick to publish this text, which was handed over to him by the Greek scholar K. Diobouniotis. The reason for this haste, according to the final remarks of Harnack, was that he wished to catch up with a new edition of the New Testament in preparation at the time, so that the specific text of Revelation could be accounted for in the critical apparatus. Hence he issued his verdict attributing the Scholia to Origen, after having studied the text for a couple of months. I myself was slower: the project occupied four years of my life, including a one-year sabbatical.

It was my initial decision to rely on Harnack’s edition for the Text of the Codex, until I was granted access to the Codex itself. Although I thought this might be of merely personal rather than scientific value, my visit to Meteora turned out to be a stunning surprise.

One cannot help but study Harnack’s edition with ambivalence. On the one hand, there is an indisputable erudition. On the other, there are fatal flaws in the text. The discrepancies between Harnack’s supposed Text of the Codex and what I actually read in the Codex myself were by no means insignificant. Too many words were misread, or misrendered, or indeed misspelled, with others being omitted altogether. Besides, the editor did not make use of typography to indicate within the text which were his own emendations. I had therefore to read the Codex ab ovo as if no edition of it had ever existed at all, since the edition available to me had turned out to be a dangerously misleading one. I saw no reason to cite the points where Harnack’s text deviates from the Codex, even though omitted or misread words are sometimes critical for identifying the author of the Scholia. Anyone interested can easily juxtapose my text with the previous one. Even before my several visits to Meteora I was however surprised that A. Harnack, C.H. Turner and other scholars had not seen some telling points which needed emendation, which I consider in detail in my edition volume of the Scholia.

Scholars engage in a selective truffle-hunting, in order to attribute severally each of the Scholia (but not every one) to a Christian theologian. It was mostly felt that since Scholia XXXVIII and XXXIX should be ascribed to Irenaeus and Scholion V is an excerpt from Clement of Alexandria, the whole point is to find out the author of each and every one of the rest of the Scholia. Of course, Origen was always the first option and in any case the discussion focussed on whether a Scholion should, or should not, be ascribed to the Alexandrian. Following Harnack, many scholars contented themselves with pointing out that Origen had used this or that term or expression, which often resulted in several of them making a hasty and triumphant ascription to him. There seems to have been a tacit assumption that it suffices to find some terms occurring in Origen in order to make up one’s mind, as if no other theologian had ever written in this world, or as if Origen had not an enormous influence on theologians such as Eusebius, Gregory of Nyssa, or Didymus; or, as if Plutarch or Alexander of Aphrodisias that had not exerted a decisive influence on Origen himself. Hence, we come upon numerous cases where Origen had introduced a peculiar and inspired term just casually in order to make a point, and this term was thereafter taken up by his enthusiasts and was put to abundantly recurring use. Renowned though his influence is, there has been far too little concern to find Origenistic influence rather than Origen. In reflecting on this narrowness of scope, I have wondered whether this is owing to the name ‘Origen’ exerting an excessive sway on research, or if in fact the real culprit is the illustrious name ‘Harnack’, the indisputable authority who seems to have exerted a commanding influence following a hasty, infelicitous ascription of these Scholia.

Besides, germane research has taken for granted that in Late Antiquity theologians were borrowing only from other theologians. A few philonians made allowance for Philo. Moreover, precisian men of the cloth throughout the empire were all too eager to discover Platonic terms in Christian writings, normally in order to satisfy the philomathy and rancour of those who appointed themselves either antipathetic critics of all theological aberration, or simply custodians of doctrinal integrity.

However, Christian theologians did not live in a vacuum and were not nurtured in a sterilized educational (let alone cultural) environment. Neither Didymus nor Theodoret nor Cassian could have ever been what they actually were, had they not studied Aristotle, Alexander of Aphrodisias, Plutarch, Galen, and Chrysippus. Defense of dogma and catechism is one thing, patrimony of erudition is quite another, and to this plain fact some Christian scholars of note were alert. For how could they possibly have expressed themselves without this stock of knowledge (or, of language, at least) and make it serviceable to their own aims and aspirations? And how could a modern scholar possibly leave research of this background out of his duties, and restrict himself only into some theologians of the time?

Conclusion

What during the last hundred years has been styled ‘Origen’s Scholia on the Apocalypse’ are in fact annotations by Cassian the Sabaite seeking to establish the divine inspiration and scriptural authority of this book. Although an Antiochene, an affiliation which denotes a specific attitude towards reading of the scriptural text, as well as towards history and Christology, and therefore towards allegorical exegesis, Cassian set out to interpret a text which par excellence requires an allegorical exegesis. He was not alone in this. Theodoret himself had engaged in allegorical approach, which was for him all but alien ground. For all the tumult surrounding allegory, Cassian took up the method that had been officially censured while eschewing Procrustean rigour. In view of the calumny surrounding the father of its Christian application, namely Origen, having recourse to allegory was a precarious proposition. Yet he carried this out while refraining from both using fanciful extrapolations, and making no mention of the term ‘allegory’ at all.

The Scholia are comments by Cassian extensively culling from Didymus’ commentary on the Apocalypse, and also include verbatim passages excerpted from Clement of Alexandria and Irenaeus –all of them coupled with ideas of his own, drawing on a variety of authors and couched in his own phraseology wherever necessary.

Cassian clearly wished to see the Revelation disentangled from prolonged dissension and at last be unanimously sanctioned as a canonical book. Yet he sought to attain this not as a sop to convention, or as acceptance of what might be thought to be sheer daemonology in disguise. The way was to show that simple and trenchant ideas of the already canonical books of scripture are also present in the apocalyptic text.

Studying Cassian’s texts throughout the Codex, one can see that he quotes freely from scripture and quite often he takes some liberties while quoting a certain passage by heart. Being a knowledgable and scrupulous scholar he must have consulted all versions available to him in order to prepare an edition on which to comment.

Discussion has shown that both Antioch and Alexandria were centres familiar to Cassian. Even if he had Antiochene sympathies, which he certainly had, he saw in Alexandria a sacrosanct patrimony handed down to all caring Christians. This means that in Cassian’s time, theologians knew each others’ works, they conversed with each other, and Antioch was prepared to cull from the Alexandrians in comprehensive expositions of a certain issue by means of composing catenae. I now have no doubt that the excerpts from Origen’s commentaries on the Psalms were composed by Antiochene hands.

Not only did Cassian care for the textual legacy of the great Alexandrian masters, but it was to them that he mainly turned in order to make up his own mind with regard to the authority of the Revelation. For all his respect for Eusebius, he does not rest content with Eusebius’ ambivalence on the question. Besides, Origen had written an entire commentary on the Revelation, which was in effect incorporated in his commentary on John. Didymus had written a commentary on the Revelation ad hoc. This concern of Cassian’s about the authority of the Revelation turns out to provide us with extensive passages from Didymus’ own commentary. Nevertheless there are also valuable exegeses by Cassian himself, too. Beyond these accounts, however, our debt for having Didymus’ own commentary, this treasure of the Alexandrian scholarship, available to us, goes entirely to a theologian of the Antiochene school.

A considerable number of the founding fathers of Christianity had accepted the Revelation. For some of them we have their own reasoning; for others, there are only testimonies by third parties. In any event, post-Nicaean Christianity had already moulded the essentials of its beliefs about the Trinitarian God and the world, and had argued them in detail. Cassian did not canvass subtler and more reflective theories elaborated during later disputation during his own era. He stood aloof from the inconclusive Christological controversy of the sixth century, which allowed little room for the dispassionate, critical study that an already disputed book required. Rather, he opted for establishing that the text takes an orthodox line on rather old issues, such as Arianism, and Gnosticism, Docetism, which nevertheless were not out of date: we know that as late as Theodoret’s lifetime, this bishop strove to convert not only Macedonians, but also Marcionites and Arians to orthodoxy.

Cassian’s first Scholion using the notion of Christ as despotes introduces both to Antiochene concerns and indeed to Theodoret’s person as the authority inspiring the fundamentals of Cassian’s thought. Hence, although Rev. 1,1 set before Scholion I actually refers to the ‘servants of God’, not to those ‘of Christ’, Cassian seized this opportunity to expound the notion of being ‘a servant of Christ’ by using the term despotes being accorded to God, at a point where ‘God’ clearly bespeaks Christ. No doubt it takes a leap in order to embark on such a line of interpretation, yet it is this jump which reveals Cassian’s priorities and constant concerns. This Scholion is indeed an illuminating text right from the start. The footnotes to this text show beyond doubt that we have a faithful quotation from the opening of Didymus’ commentary on the Apocalypse. Not quite, however. Cassian is anxious to introduce his notion of Christ, not simply God, being the despotes of all creation. Not only his Antiochene allegiances, but also the text of Revelation itself, introduce this notion which is only a casual reference in the New Testament. It is striking however that Didymus applies this appellation to no one other than God, and only a certain exception is made for simply quoting the passage of the epistle of Judas. By contrast, the epithet despotes is applied to Christ no less than two hundred times in De Trinitate, which is one more indication (of the many which are to follow in this book) that this is not a work by Didymus, but probably by Cassian.

Many, though not all, of the exegeses in the Scholia are Alexandrian, but the shroud is Antiochene. Which is why in the Scholia the terms ‘allegory’ and ‘tropology’ are not used, whereas anagoge and its cognates make a distinctive mark, which is in fact one more indication of the Antiochene tendency.

This is therefore the case of an eminent Antiochene also employing the Alexandrian sagacity. The fruits of this study attribute some crudeness to the schematisation postulating separation of the two schools in terms of essence of doctrine. Although several points in the Scholia induced scholars who reflected on them a century ago to presume that they were written by a scholar of the Alexandrian school, this was owing to the fact that Didymus was heavily quoted. The reality is that it was Cassian who quoted Didymus and Scholion I is virtually the colophon pointing to Cassian’s theological personality staunchly advancing a distinctive Antiochene approach. For all the heavy quotation from Didymus, Cassian’s train of thought is subtly yet clearly different from that of Didymus. Distinctive features of Theodoret’s thought are present throughout: the epithet theologos is applied to John the Evangelist, which Didymus never did in his indisputable works. Didymus is also the author who distinctively uses the adjective adiadochos in relation to the New Testament being ‘unsurpassed’.

The author took up definitive orthodox doctrines and adapted them to his own outlook and purpose. There is no need for new reasoning was there. Arguments against idolatry and polytheism, which are called for by the apocalyptic text, had already been available since the times of Clement, and traditional considered approaches were well-established. Had the issue of the canonicity of Revelation been entangled in the theological parlance of his day, a fatal storm would have ensued. What therefore might appear to be an amateurish or trivial theological approach in these Scholia, is in fact part of the author’s method in order to get his message across without perplexing his audience with contemporary dilemmas. The question was only the agreement of the Apocalypse with the scripture. The Scholia draw on both Testaments and show persuasively that the Book is a text which conveys the same theology as canonical writings do.

The lesson that those Scholia teach beyond their theology itself is that there was no substantial rift between Alexandria and Antioch, their different approaches notwithstanding.

Cassian draws confidently on the Cappadocians, of whom he had been taught by his tutors St. Sabas and Theodosius the Coenobiarch (who were both Cappadocian). His especial devotion to Gregory of Nyssa is all too evident. In addition, however, Leontius of Byzantium had taught him the value of the stream of thought emanating from Origen, Didymus and Evagrius. Whereas Evagrius also had important things to say about monastic ethos (which is the theme of Cassian’s monastic texts), Origen reached Cassian via Eusebius and Gregory of Nyssa as well.

Above all, however, Cassian was an offspring of Antioch, whose roots were such theologians as Diodore of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia, and whose flower and shining star was Theodoret of Cyrrhus. If therefore we wish to assess the real relation between Antioch and Alexandria, it could suffice to explore the relation of the emblematic figure of Theodoret with the tradition of Alexandria that had reached him. Our exploration has revealed that it was Theodoret and Antioch, not Alexandria, that was the true heir to Origen’s doctrinal concerns. Despite the slogan about Antioch and Alexandria denoting two rancorously divergent poles of Christian theology, it was Theodoret’s Antiochene tradition that cared for the textual legacy of such theologians as Origen and Didymus.

Our education has taught us that Theodoret was the last great scholar of Eastern Christianity. That he took exception to specific arguments advanced by Cyril, which resulted in Theodoret’s personal predicament, does not mean that he was antipathetic to the Alexandrians.

It has turned out that Theodoret was not the last great scholar of Eastern Christianity. Cassian the Sabaite emerges as a figure who demands our attention. He is the author not only of the Scholia, but also of a number of other works, which are currently branded as ‘spuria’ and wait for scholarly exertions in order to enable their eclipsed author once again to say the dictum of the Revelation, which he did not feel necessary to comment upon, since he had already proven the scriptural authority of the book: “I am he that lives and was dead; and, behold, I am alive for evermore.”